|

This mentioning by Le Jeune of who spoke Chinook Jargon also reflects the ethnic diversity in the region that is usually

"white-washed" in US American history as just a territory colonized by Anglo-Americans in the name of the imperial expansionism

later called "Manifest Destiny". Chinook Ilahee (Cascadia) was a land where Asian cultures, European cultures, Black cultures

and Pacific Islander cultures came together, often mingled and even merged with the cultures of the Native Peoples. The ethnologist

Hortatio Hale of the US Exploring Expedition of 1841 described the use of Chinook Jargon during his stay at Fort Vancouver

by a new emerging culture of Chinook Illahee in the 1840s:

"These are Canadians and half-breeds married to Chinook

women, who can only converse with their wives in this speech, and it is the fact, strange as it may seem, that many young

children are growing up to whom this factitious language is really the mother tongue, and who speak it with more readiness

and perfection than any other."

Many of these new multicultural families would eventually resettle in the French Prairie

in the Willamette Valley after the fathers of the families would terminate their employment with the Hudson's Bay Company

so as to stay with their families. But it would be wrong to assume all the men employed by the Hudson's Bay Company or spoke

Chinook Jargon were either British Canadian or French Canadian. Though many Hudson's Bay employees were French Canadians there

was also Hawai'ians and other British subjects who worked under the employment of the company and at the outposts. Sir James

Douglas, the first govenor of both the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Colony of British Columbia, for example was the

son of a Scottish sugar planter and a "free coloured woman" in Demerara, New Guiana (Guyana), was stationed at Fort Vancouver

in the 1830s before eventually being reposted farther north to foritify the north for the British Crown. Many of the "half-breeds"

Horatio Hale referred to were the Metis who themselves were a merger of French, Gaelic (Scottish) and various Native Peoples

in Canada and the Louisana. Purchase. Hawai'ian islanders made up a large part of the non-Native People to resettle in Chinook

Illahee even with a large settlement on Vancouver Island. Asian settlers specifically many Chinese would settle in the Chinook

Illahee in search of gold and later to be hired as the "cooleys" (cheap labourers) for building the intercontental railroads.

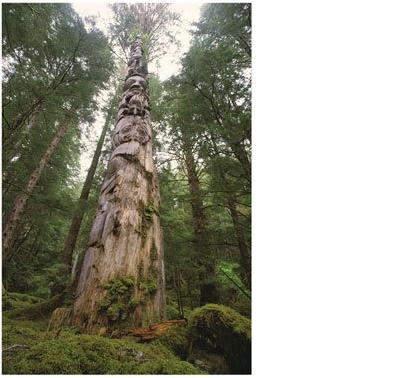

Among the various Native Peoples the evolution of Chinook Jargon would lead to it becoming the mother tongue of the generations

of different tribes forced to live together on the same reservations. During the 1800 and 1900s Chinook Jargon was the Lingua

Franca of the reservation, because different Native groups were often forced to live in the same reservation even though they

may have been of different linguistic groups or even had historical conflicts the Jargon became the means to survive and build

a new multinational culture. Chinook Jargon usually used on the reservation when English was not imposed in the boarding schools.

Chinook Jargon also would be the language in the logging camps, the Willamette hop industry and the Yukon Gold Rush where

international cultures would communicate in the Jargon for profit and survival. These confluents of cultures can still be

seen in today's Cascadia though often as a hidden history.

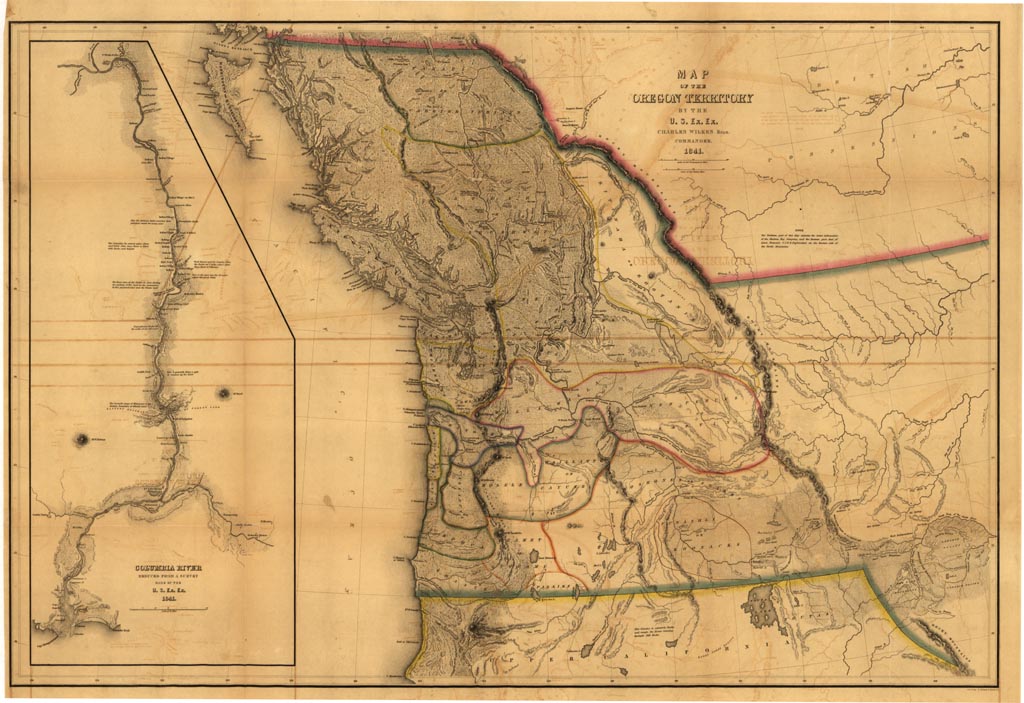

The region as a whole has been historically called Oregon.

At various times a region called Oregon has included the American states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Northern California,

Western Montana, a western portion of Wyoming up to the continental divide, the Alaskan panhandle and the Canadian province

of British Columbia as well as portions of the Yukon and Alberta west of the continental divide. The descriptive name "Pacific

Northwest" comes out of Anglo-American centered maps which displays the region in the northwest corner of the map. The region

can easily be called the NorthEast Pacific from Pacific oriented maps. Historically the whole NorthEast Pacific was the "Oregon

Country" and then became the "Oregon Territory" as it was annexed into the Atlantic Empires of Canada and the United States

of America. Eventually the name Oregon has been widdled down to one current political entity south of the Columbia River and

north of California. Some theories suggest that the name "Oregon" maybe be for the great river west of the continental divide.

A river that some Europeans thought maybe actually a "Northwest Passage" connecting the North Atlantic with the Pacific Ocean.

Some historians believe that "Oregon" was a name for the Columbia River dating back to 1765 in written accounts from the English

Army officer Major Robert Rogers. Rogers' verion of the Columbia was the Ouragon or Ourigan River in a failed written petition

in London to explore the region of the Ouragon. Some have believed this was a mistake confusing the Ouisconsink (Wisconsin

River) with the Columbia. A few historians believe "Ouragon" is from the French word for hurricane or storm. Some historians

claim "Oregon" comes from the Spanish words of oregano, oreja, and orejon or from the French word Aragon. Other theories claim

it is a name from Native people east of the Rockies.

In the 1790s, over a decade before the Lewis and Clark's expedition,

the Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie had crossed the North American continent north of Mexico in search of the Northwest

Passage. The US President Thomas Jefferson originally envisioned the land west of the Lousiana Purchase as a Republic of the

Pacific. In Jefferson's original vision this Republic of the Pacific or Pacific Republic was not to be part of the United

States, but eventually a great trading partner separate and exploring its own democratic experiment. Jefferson sent Lewis

and Clark out as ambassadors to the people west of the Rockies. When the Corps of Discovery (the original name of the Lewis

and Clark expedition) reached the Pacific Ocean there had already been European contact and even some settlement in the region.

This is not to downplay the Corp of Discovery's epic voyage, but to put it in proper perceptive as a peace-making mission,

a scientific expedition and as a trade-seeking venture. The Corp of Discovery in its brief existence perfectly represented

one interpetation of the Jeffersonian ideal. All its members including the Native American woman Sacagwea and the former slave

York had equal say in the decision making process and the right of vote. The Jeffersonian journey was one that reflected the

ideals of Enlightenment with its mission of discovery and quest for knowledge.

The following is a corrispondence from Thomas Jefferson to John Jacob Astor (whose name was used for the colony at Astoria)

on the founding of a "free and independent empire":

"To John Jacob Astor, Esq.

Monticello, November 9, 1813.

Dear Sir,—Your favor of October 18th has been

duly received, and I learn with great pleasure the progress you have made towards an establishment on Columbia river. I view

it as the germ of a great, free and independent empire on that side of our continent, and that liberty and self-government

spreading from that as well as this side, will ensure their complete establishment over the whole. It must be still more gratifying

to yourself to foresee that your name will be handed down with that of Columbus and Raleigh, as the father of the establishment

and founder of such an empire. It would be an afflicting thing indeed, should the English be able to break up the settlement.

Their bigotry to the bastard liberty of their own country, and habitual hostility to every degree of freedom in any other,

will induce the attempt ; they would not lose the sale of a bale of furs for the freedom of the whole world. But I hope your

party will be able to maintain themselves. If they have assiduously cultivated the interests and affections of the natives,

these will enable them to defend themselves against the English, and furnish them an asylum even if their fort be lost. I

hope, and have no doubt our government will do for its success whatever they have power to do, and especially that at the

negotiations for peace, they will provide, by convention with the English, for the safety and independence of that country,

and an acknowledgment of our right of patronizing them in all cases of injury from foreign nations. But no patronage or protection

from this quarter can secure the settlement if it does not cherish the affections of the natives and make it their interest

to uphold it. While you are doing so much for future generations of men, I sincerely wish you may find a present account in

the just profits you are entitled to expect from the enterprise. I will ask of the President permission to read Mr. Stuart's

journal. With fervent wishes for a happy issue to this great undertaking, which promises to form a remarkable epoch in the

history of mankind, I tender you the assurance of my great esteem and respect."

Note Jefferson did not say kill the native people or steal their lands. Instead Jefferson recommended " If they have

assiduously cultivated the interests and affections of the natives, these will enable them to defend themselves" ...

"But no patronage or protection from this quarter can secure the settlement if it does not cherish the affections of the natives

and make it their interest to uphold it."

The Jeffersonian exploration gave way to the Jacksonian reality of a vision

of expansion and the pursuit of rags to riches imagery for those lucky enough to be born of Anglo-American heritage. The British

Crown and the United States jointly occupied the Oregon Country at first. A series of meetings in Champoeg (just south of

modern Wilsonville, Oregon) called the Wolf Meetings were arranged to focus on "vermin" and pests as well as an inheritance

case. The meetings eventually made US American settlers realize that their rights were not covered by any of the judicial

systems that protected British subjects and used for Native Peoples. The growing number of US American settlers applied pressure

to form a government that represented American citizens and protected their property. There was fear by non-US citizens that

US American settlers would push for territorial annexation to the United States. Non-US residents in the Oregon Territory

had lots of reasons to be concerned about US expansion with sentiments and rhetoric similar to journalist John O'Sullivan

that publicly voicied anti-European presence in the Western Hemisphere, racial chauvinism and plenty of examples of American

expansionist policies using emigration as a method. At the same time there was pressure by Hudson's Bay Company (the British

representation in the region) to block such a vote using French Canadian and British settlers in the region. In May of 1843

the European settlers in the Oregon Country created their first "western style" government as a Provisional Government. Several

months later the Organic Act (5th of July 1843) was drawn up to create a legislature, an executive committee, a judicial system

and a system of subscriptions to defray expenses. Members of the ultra-American party insisted that the final lines of the

Organic Act would be "until such time as the USA extend their jurisdiction over us" to try to end the Oregon independence

movement. George Abernethy was elected its first and only Provisional Governor, but the opposing "party" led by Osborne Russell

favored independence. Russell proposed that the Oregon Country not join the United States, but instead become a Pacific Republic

that stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Continental Divide. Many favored the idea of independence (especially north of

the Columbia River).

The American National Mythology and Young America

The US presidential race of 1844 was filled discussion about

annexation of the Republic of Texas along with talk about annexation of the Oregon Country and California loomed over the

race for presidency. Eventually the Democratic Convention spring of 1844 put the "dark horse" candidate James Knox Polk as

the party presidential candidate. Polk, who was the Speaker of the House, ran on the campaign slogan "Fifty-four Forty or

Fight!" refering to the latitude of the most northern extent of the Oregon Country at the time. The message behind "Fifty-four

Forty or Fight!" was the push for US annexation of all of the Oregon Country or the willingness to go to war with the British

for the control of the region.

The land west of the Rockies became part of US American national mythology as a territoy the US was entitled to control

and even annex. The American newspaper, journalist John Louis O'Sullivan, was fundmental in pushing American expansionism.

His idea a divine providence of American expansionism or imperialism (later called "Manifest Destiny") was originally written

about in 1839 in his "The Great Nation of Futurity" published in the magazine The United States Democratic Review, but would

become American political rhetoric in the coming years under an expansionist president. Later O'Sullivan in the "Annexation"

(United States Magazine and Democratic Review, 1845) projects a national vision of an expansionist United States:

"Why,

were other reasoning wanting, in favor of now elevating this question of the reception of Texas into the Union, out of the

lower region of our past party dissensions, up to its proper level of a high and broad nationality, it surely is to be found,

found abundantly, in the manner in which other nations have undertaken to intrude themselves into it, between us and the proper

parties to the case, in a spirit of hostile interference against us, for the avowed object of thwarting our policy and hampering

our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted

by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions."

O'Sullivan's vision of Anglo-Saxon American

expansionism envisioned a demographic take over of Mexican California. His racist and chauvinistic vision of an Anglo-Saxon

dominance over North America is clearly reflected in his vision of an Anglo-Saxon take over of the Spanish territory of California:

"California probably, next fall away from the loose adhesion which, in such a country as Mexico, holds a remote province

in a slight equivocal kind of dependence on the metropolis. Imbecile and distracted, Mexico never can exert any real governmental

authority over such a country. The impotence of the one and the distance of the other, must make the relation one of virtual

independence; unless, by stunting the province of all natural growth, and forbidding that immigration which can alone develop

its capabilities and fulfil the purposes of its creation, tyranny may retain a military dominion, which is no government in

the, legitimate sense of the term. In the case of California this is now impossible. The Anglo-Saxon foot is already on its

borders. Already the advance guard of the irresistible army of Anglo-Saxon emigration has begun to pour down upon it, armed

with the plough and the rifle, and marking its trail with schools and colleges, courts and representative halls, mills and

meeting-houses. A population will soon be in actual occupation of California, over which it will be idle for Mexico to dream

of dominion. They will necessarily become independent. All this without agency of our government, without responsibility of

our people -- in the natural flow of events, the spontaneous working of principles, and the adaptation of the tendencies and

wants of the human race to the elemental circumstances in the midst of which they find themselves placed. And they will have

a right to independence --to self-government-- to the possession of the homes conquered from the wilderness by their own labors

and dangers, sufferings and sacrifices-a better and a truer right than the artificial tide of sovereignty in Mexico, a thousand

miles distant, inheriting from Spain a title good only against those who have none better. Their right to independence will

be the natural right of self-government belonging to any community strong enough to maintain it -- distinct in position, origin

and character, and free from any mutual obligations of membership of a common political body, binding it to others by the

duty of loyalty and compact of public faith. This will be their title to independence; and by this title, there can be no

doubt that the population now fast streaming down upon California win both assert and maintain that independence. Whether

they will then attach themselves to our Union or not, is not to be predicted with any certainty."

O'Sullivan continues

in his "Annexation" by focusing his geopolitical hunger for securing the Oregon Country and California by using the new innovations

of commerce and communications of the era in the forms of the railroad and telegraph:

"Unless the projected railroad

across the continent to the Pacific be carried into effect, perhaps they may not; though even in that case, the day is not

distant when the Empires of the Atlantic and Pacific would again flow together into one, as soon as their inland border should

approach each other. But that great work, colossal as appears the plan on its first suggestion, cannot remain long unbuilt.

Its necessity for this very purpose of binding and holding together in its iron clasp our fast-settling Pacific region with

that of the Mississippi valley -- the natural facility of the route -- the ease with which any amount of labor for the construction

can be drawn in from the overcrowded populations of Europe, to be paid in die lands made valuable by the progress of the work

itself -- and its immense utility to the commerce of the world with the whole eastern Asia, alone almost sufficient for the

support of such a road -- these coast of considerations give assurance that the day cannot be distant which shall witness

the conveyance of the representatives from Oregon and California to Washington within less time than a few years ago was devoted

to a similar journey by those from Ohio; while the magnetic telegraph will enable the editors of the "San Francisco Union,"

the "Astoria Evening Post," or the "Nootka Morning News," to set up in type the first half of the President's Inaugural before

the echoes of the latter half shall have died away beneath the lofty porch of the Capitol, as spoken from his lips."

|